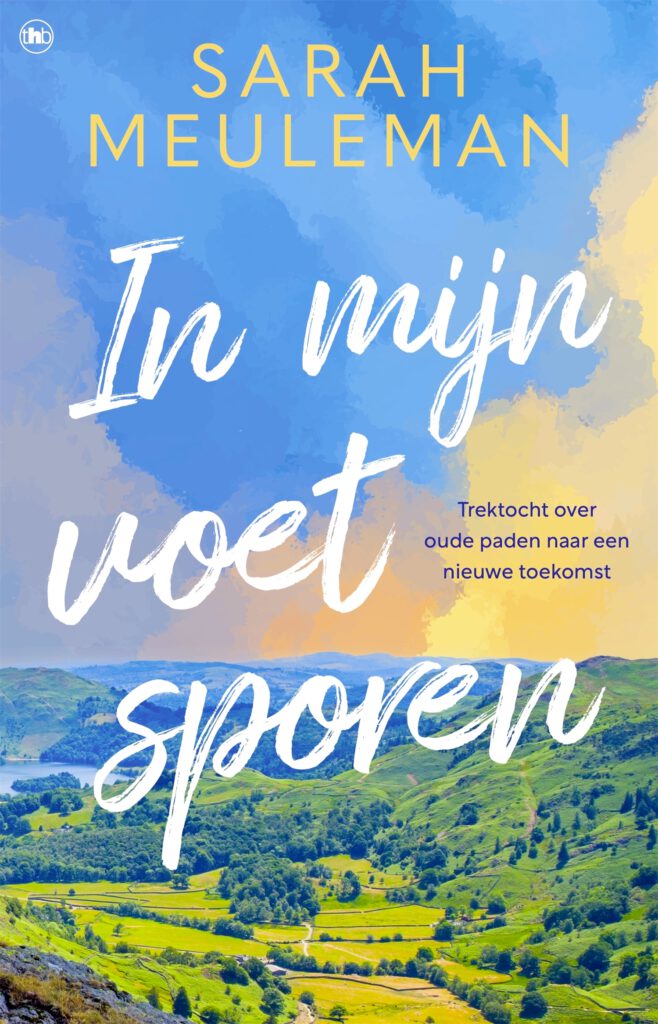

IN MIJN VOETSPOREN

Twintig jaar geleden stak Sarah Meuleman wandelend Engeland over van zee naar zee. Zonder enige wandelervaring, met een loodzware rugtas, trok ze van de Ierse Zee naar de Noordzee. De Coast to Coast wandeling is een wereldberoemd pad dat door een Britse boekhouder, Alfred Wainwright, werd bedacht.

Tijdens haar wandeltocht hield ze een dagboek bij dat ze onlangs heeft teruggevonden. Nu, in een heel andere levensfase, besluit ze in een impuls de tocht opnieuw te lopen. Als veertiger, in de voetsporen van het meisje dat ze twintig jaar geleden was. Wat is er in die twintig jaar veranderd?

Zonder voorbereiding of noemenswaardige conditie, met gemengde gevoelens, begint ze aan de lange tocht die algauw een ingrijpende wending neemt. Al wandelend herontdekt Meuleman niet alleen het landschap, maar ook zichzelf.

In mijn voetsporen is een ontroerende, hartverwarmende ode aan het wandelen, maar ook een verhaal over de keerpunten in het leven, over dromen en herinneringen, over groeien en de kracht van afscheid nemen.

Verschenen bij House of Books, 2024